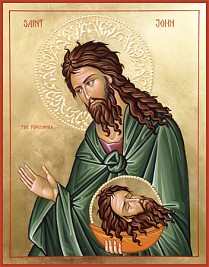

THE LIFE OF SAINT JOHN

He that was greater than all who are born of women, the Prophet who received God's testimony that he surpassed all the Prophets, was born of the aged and barren Elizabeth (Luke 1:7) and filled all his kinsmen, and those that lived round about, with gladness and wonder. But even more wondrous was that which followed on the eighth day when he was circumcised, that is, the day on which a male child receives his name. Those present called him Zacharias, the name of his father. But the mother said, "Not so, but he shall be called John." Since the child's father was unable to speak, he was asked, by means of a sign, to indicate the child's name. He then asked for a tablet and wrote, "His name is John." And immediately Zacharias' mouth was opened, his tongue was loosed from its silence of nine months, and filled with the Holy Spirit, he blessed the God of Israel, Who had fulfilled the promises made to their fathers, and had visited them that were sitting in darkness and the shadow of death, and had sent to them the light of salvation.

Zacharias prophesied concerning the child also, saying that he would be a Prophet of the Most High and Forerunner of Jesus Christ. And the child John, who was filled with grace, grew and waxed strong in the Spirit; and he was in the wilderness until the day of his showing to Israel (Luke 1:57-80). His name is a variation of the Hebrew "Johanan," which means "Yahweh is gracious."

The divine Baptist, the Prophet born of a Prophet, the seal of all the Prophets and beginning of the Apostles, the mediator between the Old and New Covenants, the voice of one crying in the wilderness, the God-sent Messenger of the incarnate Messiah, the forerunner of Christ's coming into the world (Isaiah 40:3; Mal. 3: 1); who by many miracles was both conceived and born; who was filled with the Holy Spirit while yet in his mother's womb; who came forth like another Elias the Zealot, whose life in the wilderness and divine zeal for God's Law he imitated: this divine Prophet, after he had preached the baptism of repentance according to God's command; had taught men of low rank and high how they must order their lives; had admonished those whom he baptized and had filled them with the fear of God, teaching them that no one is able to escape the wrath to come if he do not works worthy of repentance; had, through such preaching, prepared their hearts to receive the evangelical teachings of the Savior; and finally, after he had pointed out to the people the very Savior, and said, "Behold the Lamb of God, Which taketh away the sin of the world" (Luke 3:2-18; John 1: 29-36), after all this, John sealed with his own blood the truth of his words and was made a sacred victim for the divine Law at the hands of a transgressor.

This was Herod Antipas, the Tetrarch of Galilee, the son of Herod the Great. This man had a lawful wife, the daughter of Arethas (or Aretas), the King of Arabia (that is, Arabia Petraea, which had the famous Nabatean stone city of Petra as its capital. This is the Aretas mentioned by Saint Paul in II Cor. 11:32). Without any cause, and against every commandment of the Law, he put her away and took to himself Herodias, the wife of his deceased brother Philip, to whom Herodias had borne a daughter, Salome. He would not desist from this unlawful union even when John, the preacher of repentance, the bold and austere accuser of the lawless, censured him and told him, "It is not lawful for thee to have thy brother's wife" (Mark 6: 18). Thus Herod, besides his other unholy acts, added yet this, that he apprehended John and shut him in prison; and perhaps he would have killed him straightway, had he not feared the people, who had extreme reverence for John. Certainly, in the beginning, he himself had great reverence for this just and holy man. But finally, being pierced with the sting of a mad lust for the woman Herodias, he laid his defiled hands on the teacher of purity on the very day he was celebrating his birthday. When Salome, Herodias' daughter, had danced in order to please him and those who were supping with him, he promised her -- with an oath more foolish than any foolishness -- that he would give her anything she asked, even unto the half of his kingdom. And she, consulting with her mother, straightway asked for the head of John the Baptist in a charger. Hence this transgressor of the Law, preferring his lawless oath above the precepts of the Law, fulfilled this godless promise and filled his loathsome banquet with the blood of the Prophet. So it was that that all-venerable head, revered by the Angels, was given as a prize for an abominable dance, and became the plaything of the dissolute daughter of a debauched mother. As for the body of the divine Baptist, it was taken up by his disciples and placed in a tomb (Mark 6: 21 - 29). The findings of his holy head are commemorated on February 24 and May 25.

HOLY RELICS

The First Uncovering of the Head of St. John the Baptist took place in the fourth century at the time when Saint Constantine the Great and his mother, St. Helen, began restoring the holy places of Jerusalem.

The Second Finding of the Precious Head of St. John the Baptist of took place on on February 18, 452, at Emesa.

After the Seventh Ecumenical Council (787), which reestablished the veneration of icons, the head of St. John the Baptist was returned to the Byzantine capital in around the year 850. The Church commemorates this event on May 25/June 7 as the Third Finding of the Precious Head of St. John the Baptist.

His relics are kept in several places including:

- St. Demetrios Church, Neo Phaleron, Piraeus

- Benaki Museum, Athens

- Sacred Relics Room, Topkapi Museum, Constantinople (entire right arm and cranium)

- Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria

- Cetinje Monastery, Montenegro (right palm)

|

FEAST DAY(S)

The Nativity of Saint John: June 24 The Beheading of Saint John: August 29

HYMNS OF THE FEAST OF THE NATIVITY

Communion:

Thou, child, shalt be called the Prophet of the Highest: for thou shalt go before the face of the Lord to prepare his ways.

Postcommunion Hymn:

Let thy Church, O God, rejoice with gladness in the birth of blessed John Baptist: even as he made known to her the author of her new birth, Jesus Christ they Son our Lord: who liveth and reigneth with thee now and ever and unto ages of ages Amen.

HYMNS OF THE FEAST OF THE BEHEADING

Communion:

Thou hast set, O Lord, a crown of pure gold upon his head.

Postcommunion:

Grant, O Lord, that we who observe this festival of Saint John Baptist: may learn thereby to venerate aright the meaning of the wondrous mysteries which we have here received; and to rejoice abundantly in the fruits that they bring forth in us. Through Jesus Christ our Lord Who lives forever and ever and unto ages of ages Amen.

|

|